The opioid class of painkillers is so effective because they intercept pain messages to the brain, bringing relief to people experiencing severe or constant pain. In mitigating this pain, these medications bind to brain receptors, affecting voluntary functions such as breathing and heart rate. Conventional research indicates that it takes only a couple of weeks to become physically dependent. Before opioid overuse was recognized as a health epidemic, patients could receive a prescription for that class of painkillers without much scrutiny.

Why are opioids so addictive? They trigger our brains to release endorphins, the neurotransmitters that make us feel really, really good. Endorphins trick the brain into experiencing feelings of pleasure and comfort. These feelings are brief, and, when the drugs wear off, the pain can come back even stronger, more intense. This pain or discomfort makes the user want increasingly higher or more frequent doses to maintain those good feelings.

Nowadays, healthcare practitioners prescribe this class of drugs far less frequently and with much caution. Through the awareness created through this national emergency, health providers are applying more over-the-counter-, holistic-, and physical therapy-based approaches to pain management.

Despite all the awareness, we still have a seemingly insurmountable problem. According to shatterproof.org:

- Nearly 192 people die each day, In the United States, from drug overdoses.

- An addicted baby is born every 15 minutes.

- Some people overdose multiple times in their life, hanging on to overdose again, to perhaps finally get clean, or possibly succumbing to their addiction.

There is no real “demographic” for this disease. It occurs in wealthy neighborhoods and on the Native American Reservations. There do seem to be higher rates of addiction in Caucasian men, and Caucasian women see the highest rates of overdoses.

This is both a tribute and a cautionary tale…

“This disease appears to be most prevalent in the Rust Belt, where heroin is likely to be mixed with fentanyl, an exceedingly dangerous synthetic opioid.”

(shatterproof.org)

Coincidentally, the Rust Belt is where my cousin lives. And she has suffered the worst nightmare for a parent. Kimberly (we call her “Kimmy”) lost not one, but two sons to the opioid crisis. I have wanted to tell her story for a long time but didn’t know how to approach her. I didn’t know if she wanted to give strangers insight into her most profound pain and sense of loss. I cannot imagine what she has lived through and continues to manage in her daily life. I can imagine that many of my cousin’s remembrances, reflections, and thoughts as a dark, windowless room, replete with “what ifs.” There is no shortage of what-ifs.

Kimberly runs her mind-movies on an endless reel, replaying good times and conversations, and eventually moving on to the phone calls every addict’s parents dread to receive. As any parent who has experienced this excruciating loss, she wonders what she could have done to rewrite the endings of those movies. It’s our job, in telling these stories, to remind parents that despite everything you do for your children, children become adults and make their own choices. It might be easy to try to shoulder the blame because “that’s what parents do.” But we must admit that we make our own decisions about which path to take in life. Kimberly and Al gave their children a solid foundation. They were loved and had caring friends. They were good boys. But, once you walk out the door, everything can change.

This edition of Six Things is a series of vignettes that my cousin experienced as the parent of an addict. If you have an addict in your life, you may have experienced or said some of the same things as my cousin. If these thoughts ring familiar for you, you have my prayers. I hope that your movie had a happier ending.

Patrick, the Younger Brother

What if I had done something different that day?

When Kimberly’s younger son, Patrick, was a senior in high school, he experienced a bout of abdominal pain that sidelined him from playing a soccer match. After the game ended, Patrick went to the ER that evening. It was Friday before the U.S. Labor Day holiday. They could not get a doctor to see him. Between it being a holiday weekend and his physician experiencing pregnancy complications, he would not be seen by a surgeon until Sunday. An intravenous morphine drip stayed in his arm from the time they admitted him to the hospital and would remain in place all weekend. When he did eventually have surgery, the doctor nicked Patrick’s liver while removing his gallbladder and appendix.

This was probably when things changed for Patrick. When he woke up, “he was a different person,” Kimberly explains. Usually extroverted, bubbly, and talkative, after only 48 solid hours on opioids, he wouldn’t talk directly to anyone. He wanted his room dark. He was in constant pain despite his painkillers. He seemed antisocial and withdrawn. Whereas this type of surgery typically means an overnight stay, because of his complications, Patrick stayed in the hospital for a week. They sent him home with painkillers.

Kimberly says that someone she knows has tried to sue that physician. No one can locate that doctor, but the rumor is that this doctor has left the U.S. She tells me, “What if I took him to Children’s [Hospital] that night, instead of [the hospital we ended up taking him to]?” She wonders if that would have prevented him from becoming addicted in the first place. The movie rewinds every day for a heartbreaking rerun.

What if they had been honest with us?

Things seemed to be getting back on the normal track for a time. Patrick went into the Army reserves but ended up with a medical discharge. Now Kimberly wonders, “Didn’t they do a physical? Did the recruiter care that Patrick may have been using? Do they not disclose such things because they have a quota to fill? What if there was a cover-up?”

What if we were quick to notice the bad signs?

After his discharge, Patrick went home. He picks up a job here and there, but cannot focus on his tasks or stick with anything. It’s just a series of short-term jobs.

After a bit of time, the classic telltale signs appear. Jewelry and other items started missing from the house. His family didn’t notice right away, and, being clever, Patrick adept at covering his steps, kept things on the down-low. It wasn’t until his father noticed that pieces from a model train collection started to disappear that they had a sense that something was wrong.

“We were in denial, but…he’s a good kid,” Kimberly emphatically assures me, and herself. And it’s true: deep down, he was a truly nice person. He was popular. People were drawn to him and liked him. He would do anything to help friends and strangers alike.

Then pain pills started disappearing from the medicine chest. Kimberly was questioning her memory. “Maybe I got rid of them?” she wondered. But she knew better. She was making up excuses for herself and Patrick. She was mortified for her mother to find out. Kimberly’s husband will tell you that the family was in complete denial.

Heroin is cheap. Patrick could get 300 bags for some of his mother’s stolen jewelry. Despite the low price tag, Patrick was using heavily. Kimberly remembers dealers showing up at the house. On one occasion, Kimberly’s daughter went to the ATM and paid her brother’s tab. That was the last straw.

Yes, we did the whole tough-love thing.

You cannot “love your kids off drugs,” Kimberly warns. You do everything in your power to make them better.

But even your one’s family has limits on what they allow you to do to them. It got to the point where they could not live with Patrick anymore. Kimberly and her husband threw Patrick out of the house. He was invited to stay at a friend’s house, at the invitation of the friend’s parents. To this day, Kimberly doesn’t know if the parents knew the circumstances of Patrick’s eviction.

Kimberly and her husband provided Patrick with a cell phone: It was a lifeline to their son. The thought of cutting that line scared her. Yes, she knew that they should turn off his phone, but she imagined that Patrick would reach out to her for help. However, as you can guess, he used that cell phone to contact his dealers.

Kimberly believes that the hardest thing she ever had to do was to throw her son out of her house. Before their older daughter’s wedding, in fact. This caused a lot of disagreement in the family. However, Patrick managed to pull himself together to attend his sister’s wedding. It turned out to be a lovely day, and they have pictures that capture a seemingly normal family beaming at the bride and enjoying the occasion, forgetting about what seethed beneath the surface.

Rehab and repeat

Kimberly’s therapist – who knows their family well – described the almost unshakable hold that an addict’s obsession takes over. You think of the feeling you get after having a favorite indulgence such as a great single-malt whisky or some chocolate. Multiply that feeling by a factor of roughly 3,000, and that’s what you’ve got with heroin. And that factor only increases. So then comes rehab.

Patrick’s first rehab was located in Washington County, PA. His parents wanted to send him someplace where he would not know anyone. During rehab, the patient cannot come back home, back to their circle of friends and connections and dealers. Kimberly and her husband let Patrick come back home after two weeks. “He had detoxed and was a different person,” Kimberly said. They were hopeful. They thought he was clean for good. They were hopeful that things would return to the way they used to be.

As most people with addicts in their lives know, things don’t always clean up on the first try. Patrick relapsed and they ended up throwing him out of the house again. He went to live with his brother, Alex, in a town nearby. Alex could “watch” Patrick, maybe. Maybe Patrick would not go too far off the rails again. Maybe Alex could save his brother, they all hoped.

There were more admissions to rehabs. They next took Patrick to a facility where Kimberly knew some of the staff. They avoided places too close to home, for fear of the rumor mill and sideways glances. But the staff were so kind, and that was encouraging.

“I always loved to see him after detox,” Kimberly remembers. Right after detox, he was their Patrick again. He was restored to his former self.

Patrick took yet another try at rehab in the mountains of Pennsylvania. It was a beautiful setting, with opportunities to see wildlife, go fishing, and get grounded. Patrick stayed the whole time. When Kimberly and her husband were driving him home after his discharge, he said, “I’m leaving a lot on this mountain.” It was so introspective and encouraging a statement. This, they thought, could be the end of the devil that had such a hold on their son.

Then…another relapse…another rehab…

In his final rehab program, Patrick stayed over 30 days. He was flourishing and did quite well. He secured a counselor, whom he met with once each week. He progressed into a halfway house setting and was excelling in community college.

But the gravitational pull of his addiction was calling him. He met a new set of bad people and was evicted from the halfway house. He met a girl who was using and tried to kill herself. Patrick was only 21 when all this happened.

Patrick’s desperation to gain access to painkillers was taking over his life. We went so far as to cut himself and to jump off a roof. Patrick’s girlfriend called his father to tell him that Patrick cut his leg intentionally. When Patrick arrived at the hospital, the girlfriend and her mother were there, waiting for him. So were the police. Patrick left the hospital, untreated.

All through this back-and-forth, Patrick racked up quite a tab with his dealers. Before he would enter rehab, one of his uncles would settle up with his dealers so that Patrick could go into rehab with a “clean slate.”

After being kicked out of rehab, once again, Patrick moved back in with his brother, Alex. Perhaps Alex would be up to the role of “brother-fixer” once again.

Patrick, who was a charmer and never had trouble finding a companion, had a new girlfriend. Another user, but Kimberly and Al didn’t know that. The girlfriend’s mother led Kimberly to believe that Patrick got her daughter started on drugs. The girlfriend overdosed and eventually landed in rehab in Florida. As far as they know, she is sober with two children.

The “second last straw” was that Patrick was not allowed back inside his parents’ house. He was, however, invited to Thanksgiving dinner by his aunt. Patrick stayed for dinner, and he was talking to everyone. He was in a good mood, despite looking quite bad physically. He was having a nice day. It was almost like old times

Patrick died on a Friday in December, just before Christmas. A couple of days before, he visited his parents’ house. He was no longer allowed to come inside, so he stayed on the porch, talking to his dad. Kimberly dug in and would not go out to see him. Patrick told his dad he was ready to go back to rehab He wanted to try again. Kimberly regrets not going out, “…to get what would have been my last hug from him. I was trying to show him that although I loved him, I could be tough.”

Kimberly reflects on that day as the day she might have received one last hug from Patrick. It didn’t happen. She pictures how it might have been, had she surrendered and walked outside. A few days later, Patrick stopped by his father’s office Christmas party. He died the next day, and his older brother, Alex, found him.

“The system fails us.”

She so desperately wanted the “professionals” to help her son. Yes, they are adults, Kimberly acknowledges, but they are not in their right mind. She laments that the state of mental healthcare in the U.S. is “a joke.”

“This last place…they kept him for two days…only two days. I couldn’t see him. Our daughters visited and THEY agreed that it was a joke. They had him decorating the Christmas tree in the lobby. Decorating the tree…”

She is emphatic: 30-day rehab is not enough! You get false hope, and the providers make you think that everything will be okay. Some addicts stay only 14 days because of their insurance. Additionally, it is difficult to enter rehab. Unless there is an intervention, the patient has to call. The facility performs a phone intake, and they promise a bed “in maybe a couple of days.”

Alex, the big brother

In Kimberly’s words, “Alex’s journey to the end was so different.” Alex was truly affected by finding his brother. Although he had a girlfriend, he felt truly alone and floundered without Patrick.

There were some warning signs. Alex had managed to hold down a job, but he eventually lost that job. Kimberly and Al assumed that Alex and his girlfriend were heavy into pot-smoking. They had no idea, however, that Alex’s girlfriend was an opioid addict. When his girlfriend went off to rehab, and now living a routine existence without his younger brother, Alex was lost. He was at Kimberly and Al’s house every day after work.

But, even with the frequent visits, his parents had no idea Alex was using. Alex went to rehab in Ohio and had a girlfriend who was not using. Al and Alex’s girlfriend were with him when Alex checked himself into the facility. He was there two weeks but was forced to leave because he incurred a severe hand injury, after falling asleep on his hand and cutting off the blood supply to it. The plan was to see a hand specialist, get a diagnosis, then get Alex re-admitted to the rehab facility right away. The facility would not take him back, however, because he was now “clean.”

|  |

“I begged [the facility] to take him back,” Kimberly remembers, sobbing. “We told them about our other son. I have fantasies about calling [the administrator] back and telling her that Alex had died.” Thanks for nothing.

“I wanted him to test dirty so that they’d take him,” she continues. “I should have given him something. He starting using again right away. I didn’t know he was using heroin, honestly. I thought he was self-medicating with pills. You could not tell he was shooting up.”

Before his passing, Alex was pulled over by a cop while driving Kimberly’s car. He had to be tested, and Kimberly and Al didn’t get the police report until after Alex passed. They had found a needle in the car, and were requesting that Alex appear in court. What if they had gotten their hands on that police report sooner?

The day before he passed, Alex had visited his parents and helped them put together some furniture. That was just “so Alex.”

Alex was so much loved. He impressed everyone with his quiet demeanor. As a testament to his character before he became an addict, Alex’s two former girlfriends showed up for his funeral. Alex was 29 when he passed, one month shy of his 30th birthday.

During our interview, while I was on the phone, crying and laughing with my cousin, this happened…“A red bird just flew up and sat right here! Sitting here…amazing!” Kimberly knows the adage about cardinals showing up as a sign that a loved one is paying a comforting visit.

A prologue

Kimberly’s therapist tells her that Alex had extreme guilt about Patrick’s death. Perhaps there was some enablement guilt or survivor’s guilt. It’s a moot issue now, but what if Alex had been more open and willing to discuss that guilt?

Kimberly keeps a letter in Patrick’s handwriting. It says, “I love you forever and always.” That phrase, in Patrick’s hand, would become a tattoo. Alex’s fingerprint is memorialized as a tattoo on Kimberly’s wrist. When she got that tattoo, Alex’s girlfriend came along. When she got the memorial tattoo for Patrick, Alex got one, too.

I ask my cousin, “How do you get through your day?”

“I try,” she says. Kimberly is, by nature, a cheerful and giving person. “People see me smiling and laughing…” she doesn’t finish that thought, but I know what she means.

She wants and needs to be present for her three little grandsons. They keep her going. She’s their “Gigi.” “Those boys deserve the best of me,” she says.

Kimberly credits the strength and steadfast love of her daughters and her husband with helping her and Al fight through each day together. She realistically acknowledges that parents getting divorced in these situations are typical. “I need him,” she says of Al. “I have friends and family who support me. My friends let me talk about my boys.”

Kimberly and her family live their lives with candor. They do not whitewash what happened to Alex and Patrick. The obituaries are raw and honest.

Patrick Bradley Gaudino, of New Sewickley, born July 11, 1992, died Friday, December 9, 2016, after a long battle with addiction, leaving behind loving family and friends.

. . .

Alexander Mitchell Gaudino, of New Sewickley, born February 19, 1990, died January 3, 2020, after a battle with addiction, leaving behind a loving family, girlfriend, friends, neighbors, and his dogs, but joining his beloved brother, Patrick, in Heaven.

A note from Maura

I realize that it has been a long time since you’ve heard from me here at Six Things. I interviewed my cousin in September 2020 for this post. I have dithered about how to approach this story. I wanted this to be a tribute to Patrick and Alex, but I also wanted this to be a celebration of the strength and resilience of my cousin and her family.

I am a writer. I write all kinds of things for a living and I hardly ever get writer’s block. However, this post was anomalous to most of my writing experiences. I would sit down, and start crafting the story, but it never came out the way I wanted. I would recount the notes I took. I wept real tears as I typed each letter of this truly sad story. I went back to the drawing board, several times, scrapping several other versions of this story. I wanted to get it just so…so right…I fretted about leaving out a pertinent detail. I obsessed over the timeline. I second-guessed my gamble of getting inside Kimberly’s head.

In the end, I decided that the best way to tell the story was to just tell the damn story. I brain-dumped, honed, and fine-tuned. After all this time, Kimberly probably thought I’d forgotten my promise to memorialize Patrick, Alex, and their family’s struggles.

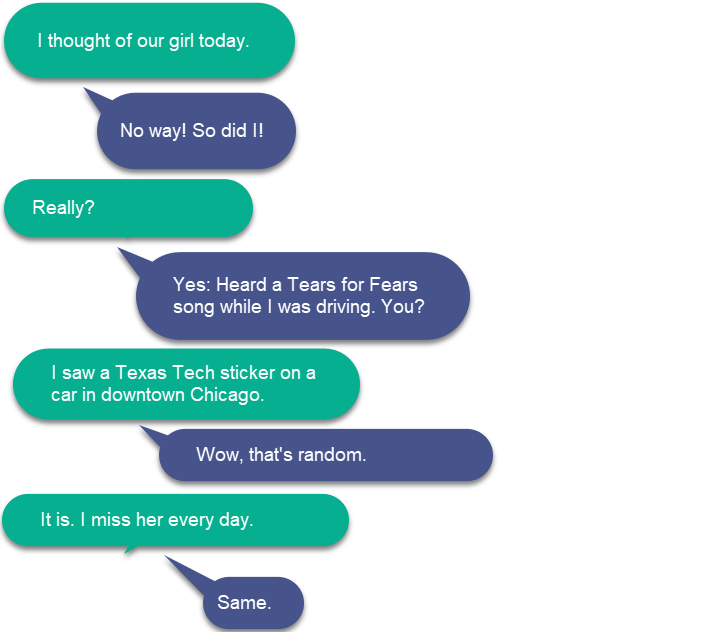

Then, just today, I contacted my cousin to tell her that I’d finished. And I got the blessing I hoped to receive…

Got it! I’m so excited to read it. ♥

I hope it does everyone justice. Let me know if we

need to hop on the phone to clean up anything.

Maura, I’m speechless. I’m reading this and it is my life

with your perfect words. It is so beautifully

written. I’m crying and smiling

all at the same time. Thank you so much. ♥

You are such a special writer (and cousin). I

Can’t thank you enough.

Omg…this makes me so happy! We did it!

Maura, it’s perfect.

I won’t share the rest of what we said to one another. That’s between us.

Rest in peace, Alex and Patrick.